- Home

- Campbell McGrath

Nouns & Verbs Page 6

Nouns & Verbs Read online

Page 6

thanks to our

Schaefer customers

for their loyalty

and support.

It is brewed in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

It knows its place.

It wears its heart on its sleeve

like a poem,

laid out like a poem

with weak line endings and questionable

closure. Its idiom

would not be unfamiliar

to a Soviet film director,

its emblem a stylized stalk

of bronzed wheat,

circlets of flowering hops

as sketched by a WPA draftsman

for a post office mural in 1934.

It conjures a forgotten social contract

between consumers and producers,

a world of feudal fealty—

the corporation

is your friend, your loyalty

shall be rewarded—a vision

of benign paternalism

last seen in Father Knows Best

and agitprop depictions of Mao

sharing party wisdom with eager villagers,

bestowing avuncular unction.

It was, once, the one

beer to have

when you’re having more than one,

slogan and message

outdated as giant ground sloths roaming

the forests of Nebraska,

irrecoverable

as the ex-cheerleader

watching her toddler eat handfuls of sand

at the playground

considers that lost world of pompoms

and rah-rah-let’s-go-team

to be.

It has earned no lasting portion of glory.

It has eaten crow

and humble pie. Long before it was faded

by the sun it appeared

faded by the sun, gathering dust

in the corner

of the bodega or the county store,

cylindrical, handy, holsterable,

its modesty honestly

come by, possessing the courage

of its simple convictions

like the unsuspected gunfighter

emerging from shadow

to defend the weak from tyranny.

And if we have moved forward,

unmasking the designs of the regime

upon our fertile valley,

learning to litigate against the evil sheriff,

such knowledge has left a bitter taste

in our mouths,

and if this can of beer

deserves our attention

it is as a reminder of what it meant

to speak without hypocrisy,

to live unironically,

to be sincere.

Thin, rice-sweet, tasting of metal

and crisp water,

it is no worse than many,

and if it is not an elixir it might serve

as an occasional draft

of refreshment and self-knowledge.

It was established in the United States in 1842.

It contains 12 fl. oz.

Store in a cool place

and drink responsibly.

Poetry and the World

In the world of some poets

there are no Cheerios or Pop-Tarts, no hot dogs

tumbling purgatorially on greasy rollers,

only chestnuts and pomegranates,

the smell of freshly baked bread,

summer vegetables in red wine, simmering.

In the world of some poets

lucid stars illumine lovers

waltzing with long-necked swans in fields

flush with wildflowers and waving grasses,

there are no windowless classrooms,

no bare, dangling bulbs,

no anxious corridors of fluorescent tubes.

In the world of some poets

there is no money and no need

to earn it, no health insurance,

no green cards, no unceremonious toil.

And how can we believe in that world

when the man who must clean up after the reading

waits impatiently outside the door

in his putty-colored service uniform,

and the cubes of cheese at the reception

taste like ashes licked from a bicycle chain,

when the desktops and mostly empty seats

have been inscribed with gutter syllabics

by ballpoint pens gripped tight as chisels,

and the few remaining students are green

as convalescents narcotized by apathy?

But—that’s alright. Poetry

can handle it.

Poetry is a capacious vessel, with no limits

to its plasticity, no end to the thoughts and feelings

it can accommodate,

no restrictions upon the imaginings

it can bend through language into being.

Poetry is not the world.

We cannot breathe its atmosphere,

we cannot live there, but we can visit,

like sponge divers in bulbous copper helmets

come to claim some small portion

of the miraculous.

And when we leave we must remember

not to surface too rapidly,

to turn off the lights in the auditorium

and lock the office door—there have been thefts

at the university in recent weeks.

We must remember not to take the bridge

still under construction, always under construction,

to stop on the causeway for gas

and pick up a pack of gum at the register,

and a bottle of water,

and a little sack of plantain chips,

their salt a kind of poem, driving home.

Girl with Blue Plastic Radio

The first song I ever heard was “The Ballad of Bonnie and Clyde.”

There was a girl at the playground with a portable radio,

lying in the grass near the swing set, beyond the sun-lustred aluminum slide,

kicking her bare feet in the air, her painted toenails—toes

the color of blueberries, rug burns, yellow pencils, Grecian urns.

This would be when—1966? No, later, ’67 or ’68. And no,

it was not the very first song I ever heard,

but the first that invaded my consciousness in that elastically joyous

way music does, the first whose lyrics I tried to learn,

my first communication from the gigawatt voice

of the culture—popular culture, mass culture, our culture—kaboom!—

raw voltage embraced for the sheer thrill of getting juiced.

Who wrote that song? When was it recorded, and by whom?

Melody lost in the database of the decades

but still playing somewhere in the mainframe cerebellums

of its dandelion-chained, banana-bike-riding, Kool-Aid-

addled listeners, still echoing within the flesh and blood mausoleums

of us, me, we, them, the selfsame blades

of wind-sown crabgrass spoken of and to by Whitman,

and who could believe it would still matter

decades or centuries later, in a new millennium,

matter what we listened to, what we ate and watched, matter

that it was “rock ’n’ roll,” for so we knew to call it,

matter that there were hit songs, girls, TVs, fallout shelters.

Who was she, her with the embroidered blue jeans and bare feet,

toenails gilded with cryptic bursts of color?

She is archetypal, pure form, but no less believable for that.

Her chords still resonate, her artifacts have endured

so little changed as to need no archeological translation.

She was older than me, worldly and self-assured.

She was, al

ready, a figure of erotic fascination.

She knew the words and sang the choruses

and I ran over from the sandbox to listen

to a world she cradled in one hand, transistorized oracle,

blue plastic embodiment of our neo–Space Age ethos.

The hulls of our Apollonian rocket ships were as yet unbarnacled

and we still found box turtles in the tall weeds and mossy grass

by the little creek not yet become what it was all becoming

in the wake of the yellow earthmovers, that is:

suburbia. Alive, vibrant, unself-consciously evolving,

something new beneath the nuclear sun, something new in the acorn-scented dark.

Lived there until I was seven in a cinder-block garden

apartment. My prefab haven, my little duplex ark.

And the name of our subdivision was

Americana Park.

Wheel of Fire, the Mojave

What is this white intensity

swallowing me as the night swallows and now disgorges

only Jonah was rocked and the night

is sorrowful music

but this is something else? What is this absence,

immersion as faith is a kind of immersion,

a thirst for light in the true air?

Look at the sun’s jailbreak over the violent

walls. I’ve driven all night

to find myself here. Look at the gypsum desert,

elements scattered like 7-Elevens all the way to Death Valley,

the way L.A. reaches into it, one hundred miles or more.

I’m talking about America, the thing itself,

white line unreeling, pure distance, pure speed.

I’ve driven all night

from fear of the darkness that would seize me if I stopped,

even coffee at a truck stop, even water. Look

at the wraiths of stars,

Buick Electras rusting in the freight meadow.

It is the ghost of the light that moves me.

I’m talking about the half-seen,

dawn and evening, desert orchids,

coyotes coming down to the river to drink.

I’m talking about the thing itself,

what rises in the night like anger or grief,

language-less, blistering and overbrimming

as a river coming down from the mountains

to die in the sinks of rushes and alkali,

the absolute purity of light or intention,

memory of grace, seagulls canting windward

above the Great Salt Lake—

the sun, the desert,

the weight of the light is staggering—

until even the flesh of our days falls away,

ash from a cone, fruit from a stone. Even now

when the whirling miraculous

wheel in the sky has risen and vanished at first light,

gears of a huge engine, starlings

drunk on oxygen—

when the wheel

is gone and I am alone with the willows

at the edge of the utterly desolate

Mojave River.

I’ve driven all night toward the basin

of angels. I’ve driven all night without understanding

anything, need or desire, this desert, neon

signs remorseless as beacons.

I’m talking about America.

I’m talking about loneliness, the thing itself.

I’ve driven all night to find myself

here. Look around you,

even now look around you.

Dawn breaking open the days like jeweled eggs,

Joshua trees crippled by this freakish rain of light.

Consciousness

An obsessive compulsion, a ring of keys,

a sequence of numerals to roll the tumblers

and open the golden vault, a web, a blizzard,

a stochastic equation to generate song.

It goes on. There is no satiety mechanism

in the market system, in the agora of thought.

We cannot bloom, cannot flower,

cannot crystallize into coal or diamond

or disassemble ourselves into pure melody.

Alone in the ruined observatory we stand

surrounded by astral bodies, glittering

milk-folds of star creation we stutter to name

but still we cannot burn our fingerprints

into the void. Into. The. Saints of it, myths of it,

cloister, waterwheel, winged lion, myrrh.

Knots of olive wood in a beached rowboat

over which to roast the tiny silver fish

delicious with salt and lemon. Marooned, then,

but well fed on the substance of this world.

And still forsaken. And still hungry.

Smokestacks, Chicago

To burn, to smolder with the jeweled incendiary coal

of wanting, to move and never

stop, to seize, to use,

to shape, grasp, glut, these united

states of transition, that’s

it, that is it,

our greatness, right

there. Dig down the ranges, carve out

rivers and handguns and dumps, trash it,

raze it, torch

the whole stuck-pig of it. Why

the fuck not? Immediately I am flying

past some probably

pickup truck with undeniable motor

boat in tow, a caravan

of fishermen no less, bass and bronze eucalyptus scars,

red teeth of erosion click-clacking

their bitterness. And

the sports fans

coming home through a rain

of tattered pompoms. And the restless

guns of suburban hunters shooting

skeet along the lake. Desire is

the name of every vessel out there, but

I think the wind that drives them

is darker. I think I see

the tiny sails are full of hate

and I am

strangely glad. Don’t stop,

hate and learn to love your hatred,

learn to kill and love the killing of what you hate,

keep moving,

rage, burn, immolate. Let the one

great hunger flower

among the honeysuckle skulls

and spent shells

of the city. Let longing

fuel the avenues of bowling alleys and flamingo

tattoos. Let sorrow glean the shards

of the soul’s bright jars

and abandoned

congregations. Harvest moon

above the petrified

forest of smokestacks.

The Burning Ship

No room for regret or self-doubt in art,

doubt but not self-doubt. The ship hauls anchor,

the kerosene lantern flickers and goes out,

voices in the pitch black swell with anger

as shipmates mistake each other for enemies.

The lantern spills, the pilot drops a lit cigar.

Tragedy ensues and engenders more tragedy.

If only the moon could see, if only the stars

had been granted the power of speech.

But the blind remain blind, the voiceless mute.

The burning ship threads its way between reefs

in the darkness. Doubt, but not self-doubt.

The Future

I would speak to it as to a stream in the forest

where infant ferns grow shapely as serpents or violins.

I would surrender to it if I could drift among the stars

as among a cloud of milkweed spores, or jellyfish.

Years turn, like autumn leaves; they pass,

and we number them, like galaxies or symphonies,

when we should honor them with names,

&nbs

p; like hurricanes, or the craters of the moon.

What will Arcturus ever mean to me

compared to these years—1962, 1986, 2005?

They march beside me like siblings,

they are more intimate than lovers,

they do not turn back when I fall behind.

The future watches us and marvels

at our inability to comprehend it.

Even Einstein only glimpsed its shores,

like Magellan, planting small vineyards

at the edge of the ice, like Erik the Red.

To view it plainly we would need to evict

the self from its rough settlement,

to strip the bark from our limbs and branches,

to reside in a place where atoms and stars

resemble shy animals learning to eat from our hand.

Only then would the future, like a lonely hermit,

find its way to that clearing by the stream in the forest,

and sit beside us on a mossy stone, and listen.

The Zebra Longwing

Forty years I’ve waited,

uncomprehending,

for these winter nights

when the butterflies

fold themselves like paper cranes

to sleep in the dangling

roots of the orchids

boxed and hung

from the live oak tree.

How many there are.

Six. Eight. Eleven.

When I mist the spikes

and blossoms by moonlight

they stir but do not wake,

antennaed and dreaming

of passionflower

nectar. Never before

have they gifted us

in like manner, never before

have they stilled their flight

in our garden. Wings

have borne them away

from the silk

of the past as surely

as some merciful wind

has delivered us

to an anchorage of such

abundant grace,

Elizabeth. All my life

I have searched, without knowing it,

for this moment.

Nights on Planet Earth

Heaven was originally precisely that: the starry sky, dating back to the earliest Egyptian texts, which include magic spells that enable the soul to be sewn in the body of the great mother, Nut, literally “night,” like the seed of a plant, which is also a jewel and a star. The Greek Elysian Fields derive from the same celestial topography: the Egyptian “Field of Rushes,” the eastern stars at dawn where the soul goes to be purified. That there is another, mirror world, a world of light, and that this world is simply the sky—and a step further, the breath of the sky, the weather, the very air—is a formative belief of great antiquity that has continued to the present day with the godhead becoming brightness itself: dios/theos (Greek); deus/divine/Diana (Latin); devas (Sanskrit); daha (Arabic); day (English).

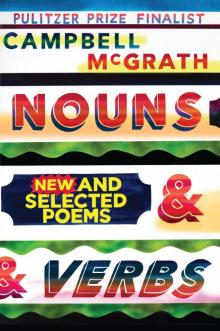

Nouns & Verbs

Nouns & Verbs