- Home

- Campbell McGrath

Nouns & Verbs Page 5

Nouns & Verbs Read online

Page 5

until each white-fingered branch, each dew-glazed bud,

is lit from within.

2

Oregon state is mighty fine

if you’re hooked on to the power line.

—WOODY GUTHRIE

What Woody Guthrie leaves out of his song

about the Grand Coulee Dam

is not the flumed bulk

shouldering clouds and mountains aside.

Neither is it the beauty of the black river;

the smell of horses in rain in the wild gorge country;

the catalogue of states gripped by dust and Depression—

Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Georgia, Tennessee;

nor even the old desire to tame the wilderness,

to shape river and mountain and desert to man’s will.

What’s never mentioned, left unsung,

is the nature of that time

when a dam was something to sing about—

an attitude of profound wonder, honed by despair,

humming through high-tension wires

all across the country,

technology’s promise

brought to every town and ranch and farm—not only

along the sinuous Columbia choked with logs,

but everywhere, all over this land, from California

to the New York island. An era

finding voice in a song about e-leca-tri-cy-tee.

A vast, implicit history, east and west,

growth and opportunity and inequality,

crystalline in the moment—

just as a hologram, when shattered, retains

the image of the whole in every shard and fragment—

from Maine to Oregon,

from Plymouth Rock to the Grand Coulee Dam

where the water runs down.

3

What Ansel Adams leaves out

is neither song, stone, nor innuendo

of light cascading through rain-laced aspens.

Lost at the base of Blanca Peak

are two figures: one pulls up stakes

while the other stirs a pot of coffee with a tin spoon.

They hike all day along the ridgeline

and at evening make camp in a valley

where a thin stream is marked by alder

and gooseberries. They build a fire

to cook macaroni and cheese, and heat cans of beans

in the coals for dinner. Late at night,

in contrast to all rules of composition,

they beat a riven, smoldering log with pine boughs

sending sparks like clouds and flocks of birds

and winter storm in the valley

rising up to the stars, splinters of light or stone,

innumerable and inseparable.

Books

Books live in the mind like honey inside a beehive,

that ambrosial archive, each volume sealed in craft-made paper,

nutritive cells, stamen-fragrant, snug as apothecary jars.

Like fossilized trilobites, or skulls in a torchlit catacomb

beneath an ancient city, Byzantium or Ecbatana,

or Paris at the end of April when vendors set their folding tables

filled with lily-of-the-valley beside every Métro entrance,

and the women, coming home from work or market,

scented already with the fugitive perfume of muguets,

carry handheld bouquets like pale tapers

through the radiant, rain-washed streets at sunset.

And then it is night, half the world ruled by dreams

from which arise narrative forms—riddles, fables, myths—

as mist lifts from mountain valleys in autumn,

as steam belches from fumaroles in benthic trenches

to whose sulfuric cones strange life-forms cling,

chrome-green crabs and eyeless shrimp, soft-legged starfish

sung to sleep by that curious cousin of the hippopotamus,

the whale, who, having first evolved from ocean to land

in the ever-eventful Cretaceous, thought better of it,

returning, after millions of years, to scholarly contemplation

in the mesomorphic, metaphysical library of the sea.

Late Spring

The kingdom of perception is pure emptiness.

—PO CHÜ-I

1.

I have faltered in my given duty.

It is a small sacrilege, a minor heresy.

The nature of the duty is close attention

to the ivy and its tracery on riled brick,

the buckled sidewalk, the optimistic fern,

downed lilacs brown as coffee grounds,

little twirled seedwings falling by the thousands

from the maples in May wind,

and the leaves themselves

daily greener in ripening sunlight.

To whom is their offering rendered,

and from whom derived,

these fallen things

urging their bodies upon the pavement?

There is a true name for them,

a proper term, but what is it?

2.

Casting about, lachrymose, the branches

of the trees at 4 A.M.

flush with upthrust flowers,

like white candles in blackened sconces.

All day I was admonished

to admire the beauty of this single peony

but only now, in late starlight,

do I crush its petals to my face.

Elemental silk dimmed to ash,

reddening already to the brushstroke of dawn,

its fragrance is a tendril

connecting my mind to the rain,

a root, a tap, a tether.

Such is the form of the duty,

but which is its officer,

the world or the senses?

The many languages of birds now,

refusing to reconcile,

and clouds streaming out of the darkness

like ants to the day’s bound blossom.

Spicer

Then sadness came upon them. Memories of love

or sorrow, favorite cats, barnyard animals,

dirt where called for

and all the appropriate longings, lusts, self-pity,

even rage at some tyrannical lapse of manners

over Chinese food—just so each chosen beam or ray,

each this, each that, so special and unique:

Grandma’s ribbon of Kansas whalebone,

hedge clippers from the root cellar

of the dazed horticulturist. Time passes. The years

groove one by one round the garlanded Maypole,

and the presence of natural totems

bears a significant impact on the order of our lives,

dew-struck daylilies dieseling skyward,

the beauty of the crab apple tree against a derelict wall,

each fruit a form of grace or an admission

of human frailty. You’re the MSG in my shark’s fin soup,

but I yam what I yam, sweet potato.

The rage of our days rises like lobster claws

doused in fake butter

from a seafood restaurant chain,

but in the end, dancing, we unfasten

our rainbow suspenders and lie down with death,

mongrel death, gym coach death

tossing dodgeballs of extirpation, turning somersaults

of grief on misery’s wrestling mats. Everything passes,

rain dissolving a lost box of cough drops, so many

Dutch Apple Pop-Tarts in the heart’s toaster oven.

Things are like that. We’re like that,

alone together, ignorant of shadows as cardamom

or star anise reveling in sunlight,

wild seeds blind to the spicer’s approach.

Invitations

To rhetoric: quarry me

/> for the stones of such tombs as may rise

in your honor.

To molecules: let me be carbon.

To the burners of bones: let me be charcoal.

To the drosophila: declaim to me

of finger bananas.

To eyes: that they might look askance

in the darkness and find me.

Emily and Walt

I suppose we did not want for love.

They were considerate parents, if a bit aloof,

or more than a bit. He was a colossus

of enthusiasms, none of them us,

while she kissed our heads and mended socks

with a wistful, faraway look.

She might have been a little, well, daft.

And he—Allons, my little ones, he’d laugh,

then leave without us.

And those “friends” of his!

Anyway, he’s gone off to “discover

himself” in San Francisco, or wherever,

while she’s retired to the condo in Boca.

We worry, but she says she likes it in Florida;

she seems, almost, happy. I suppose they were

less caregivers than enablers,

they taught by example, reading for hours

in the drafty house and now the house is ours,

with its drawers full of junk and odd

lines of verse and stairs that ascend to god

knows where, belfries and gymnasia,

the chapel, the workshop, aviaries, atria—

we could never hope to fill it all.

Our voices are too small

for its silences, too thin to spawn an echo.

Sometimes, even now, when the night wind blows

into the chimney flue

I start from my bed, calling out—“Hello,

Mom and Dad, is that you?”

Florida

There is no hope of victory in this garden.

Bent to the lawn, I acknowledge defeat

in every blade of St. Augustine

grass destroyed by intractable chinch bugs.

Hours on end I pull the woody roots

of dollar weed from the soil. At night I dream

of vegetable genocide, so deep, so abiding,

has my hatred for that kingdom grown.

Near dawn I hear the scuttle of fruit rats

returning to their nest within our wall;

they walk the tightrope of the phone wires at dusk,

leap like acrobats into limbs of heavy citrus.

Something larger inhabits the crawl space,

raccoon or opossum, purple carapace

of the land crab emerging from its burrow.

On a branch, green caterpillars thick as a finger,

from which will rise some terrible night moth.

The snails leave calcified notice of their trespass;

in the rain they climb the hibiscus and wait.

I labor in sunlight, praying for stalemate.

California Love Song

To ride the Ferris wheel on a winter night in Santa Monica,

playing nostalgic songs on a Marine harmonica,

thinking about the past, thinking about everything

Los Angeles has ever meant to me, is that too much to ask?

To kiss on the calliope and uproot world tyranny

and strum a rhythm guitar Ron Wood would envy,

to long for the lost, to love what lasts, to sing

idolatrous praises to the stars, is that too much to ask?

Arm in arm to gallivant, to lark, to crow, to bask

in a wigwam of circus-colored atomic smog,

to quaff a plastic cup of nepenthean eggnog

over one more round of boardwalk Skee-Ball,

to trade my ocean for a waterfall,

to live with you or not at all, is that too much to ask?

Angels and the Bars of Manhattan

for Bruce Craven

What I miss most about the city are the angels

and the bars of Manhattan: faithful Cannon’s and the Night Cafe;

the Corner Bistro and the infamous White Horse;

McKenna’s maniacal hockey fans; the waitresses at Live Bait;

lounges and taverns, taps and pubs;

joints, dives, spots, clubs; all the Blarney

Stones and Roses full of Irish boozers eating brisket

stacked on kaiser rolls with frothing mugs of Ballantine.

How many nights we marked the stations of that cross,

axial or transverse, uptown or down to the East Village

where there’s two in every block we’d stop to check,

hoisting McSorley’s, shooting tequila and eight-ball

with hipsters and bikers and crazy Ukrainians,

all the black-clad chicks lined up like vodka bottles on Avenue B,

because we liked to drink and talk and argue,

and then at four or five when the whiskey soured

we’d walk the streets for breakfast at some diner,

Daisy’s, the Olympia, La Perla del Sur,

deciphering the avenues’ hazy lexicon over coffee and eggs,

snow beginning to fall, steam on the windows blurring the film

until the trussed-up sidewalk Christmas trees

resembled something out of Mandelstam,

Russian soldiers bundled in their greatcoats,

honor guard for the republic of salt. Those were the days

of revolutionary zeal. Haughty as dictators, we railed

against the formal elite, certain as Moses or Roger Williams

of our errand into the wilderness. Truly,

there was something almost noble

in the depth of our self-satisfaction, young poets in New York,

how cool. Possessors of absolute knowledge,

we willingly shared it in unmetered verse,

scavenging inspiration from Whitman and history and Hüsker Dü,

from the very bums and benches of Broadway,

precisely the way that the homeless

who lived in the Parks Department garage at 79th Street

jacked into the fixtures to run their appliances

off the city’s live current. Volt pirates,

electrical vampires. But what I can’t fully fathom

is the nature of the muse that drew us to begin with,

bound us over to those tenements of rage

as surely as the fractured words scrawled across the stoops

and shuttered windows. Whatever compelled us

to suspend the body of our dreams from poetry’s slender reed

when any electric guitar would do? Who did we think was listening?

Who, as we cried out, as we shook, rattled, and rolled,

would ever hear us among the blue multitudes of Christmas lights

strung as celestial hierarchies from the ceiling? Who

among the analphabetical ranks and orders

of warped records and secondhand books on our shelves,

the quarterlies and Silver Surfer comics, velvet Elvises,

candles burned in homage to Las Siete Potencias Africanas

as we sat basking in the half-blue glimmer,

tossing the torn foam basketball nigh the invisible hoop,

listening in our pitiless way to two kinds of music,

loud and louder, anarchy and roar, rock and roll

buckling the fundament with pure, delirious noise.

It welled up in us, huge as snowflakes, as manifold,

the way ice devours the reservoir in Central Park.

Like angels or the Silver Surfer we thought we could

kick free of the stars to steer by dead reckoning.

But whose stars were they? And whose angels

if not Rilke’s, or Milton’s, even Abraham Lincoln’s,

“the better angels of our nature” he hoped would emerge,

air-swimmers descendi

ng in apple-green light.

We worshipped the anonymous neon apostles of the city,

cuchifrito cherubs, polystyrene seraphim,

thrones and dominions of linoleum and asphalt:

abandoned barges on the Hudson mudflats;

Bowery jukes oozing sepia and plum-colored light;

headless dolls and eviscerated teddy bears

chained to the grilles of a thousand garbage trucks; the elms

that bear the wailing skins of plastic bags in their arms all winter,

throttled and grotesque, so that we sometimes wondered

walking Riverside Drive in February or March

why not just put up cement trees with plastic leaves

and get it over with? There was no limit to our capacity for awe

at the city’s miraculous icons and instances,

the frenzied cacophony, the democratic whirlwind.

Drunk on thunder, we believed in vision

and the convocation of heavenly presences summoned

to the chorus. Are they with us still? Are they

listening? Spirit of the tiny lights, ghost beneath the words,

numinous and blue, inhaler of bourbon fumes and errant shots,

are you there? I don’t know. Somehow I doubt we’ll ever know

which song was ours and which the siren

call of the city. More and more, it seems our errand

is to face the music, bring the noise, scour the rocks

to salvage grace notes and fragmented harmonies,

diving for pearls in the beautiful ruins,

walking all night through the pigeon-haunted streets

as fresh snow softly fills the imprint of our steps.

OK, I’m repeating myself, forgive me, I’m sure brevity

is a virtue. It’s just this melody keeps begging to be hummed:

McCarthy’s, on 14th Street, where the regulars drink

beer on the rocks and the TV shows Police Woman

twenty-four hours a day; the quiet, almost tender way

they let the local derelicts in to sleep it off

in the back booths of the Blue & Gold after closing;

and that sign behind the bar at the Marlin, you know

the one, hand-lettered, scribbled with slogans of love and abuse,

shopworn but still bearing its indomitable message

to the thirsty, smoke-fingered, mood-enhanced masses—

“Ice Cold Six Packs To Go.” Now that’s a poem.

Ode to a Can of Schaefer Beer

We would like to

express sincere

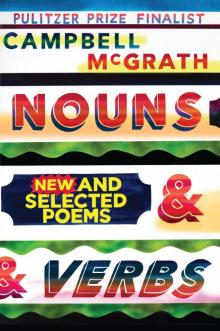

Nouns & Verbs

Nouns & Verbs