- Home

- Campbell McGrath

Nouns & Verbs Page 8

Nouns & Verbs Read online

Page 8

The Leatherback

I’m still slogging Sam’s surfboard across the sand when the boys race off to see what the commotion up the beach is all about, and by the time I get close they’ve run back to report, a sea turtle, a leatherback, the biggest of them all, we’ve never seen one before, but there’s a problem, it’s injured, they’ve already loaded it into the back of the Fish & Game Department pickup truck as the local cops pointlessly holler to stand back, stand back, and it is truly huge, like an old sequoia log, like the barnacled hull of an overturned rowboat, one of the rangers says it is probably eighty years old, and the boys say its fins are all chopped up by a boat, but the ranger says no, a knife, and now I can see sinewy stumps where the flippers should be, gray flesh marbled with milk-white fluid, sickening, I turn away, it must have washed here from some place where turtles are still a food source, the Bahamas are less than a hundred miles east, there’s a strong wind blowing Portuguese men-o’-war up on the beach, sea turtles eat jellyfish, the tentacles blind them as they age, these waves have brought us all here today, some surfers already out, others in the crowd talking about the turtle, I’m turning to head back when I see the bad look on Elizabeth’s face, some of the white-haired retirees from the next building are telling her the full story, it crawled from the ocean at dawn, it didn’t lay eggs, it didn’t swim away, they thought it was old, maybe sick, they called the police, the fishermen from the jetty wandered over to look, one man rode it like a horse, before it’s clear what’s happened, or why, a fishing knife emerges to saw through the rubbery, elephant-thick skin, three flippers gone before anyone stops him, the senior citizens are shouting out, hey, no!, accosting him, what are you doing? why did you do this? and he: for soup, some of the old people are crying, they chase him away, get lost!, you’re crazy, how would you feel if we cut your arm off like that?, some of the fishermen laughed, some shook their heads, the police arriving helpless, uninformed, it’s more than I can handle, honestly, I turn away, I am trembling not with anger but with shame, the ranger truck spins its wheels and bogs down in soft sand having traveled perhaps fifty feet, it takes an hour before a tractor comes to tow them clear, the giant turtle is that heavy, what is there to say?, eighty years old, for soup, that milky extrusion—was it blood?, as I dive into the water I am thinking how generous the ocean is in its forgiveness, I am thinking at least I never looked into its eyes.

Squid

What could ever equal their quickening, their quicksilver jet pulse of arrival and dispersal, mercurial purl and loop in the fluid arena of the floodlight toward which they had been lured like moths to their undoing? We were eighteen that summer, Mike and I, working on an old Greek-registered freighter carrying holds full of golden corn to Mexico, corn that flowed like ancestral blood through the continent’s veins and south, down the aorta of the Mississippi, to be loaded for transport across the Gulf. From Baton Rouge it was hours threading the delta and one long night suspended between stars and the galaxies of luminescent plankton stirred up in our wake and then a week at anchor awaiting a berth in the harbor at Veracruz. By the third day the sailors had grown so restless the Captain agreed to lower the gangway as a platform from which to fish for squid, which was not merely a meal but a memento of home flashing like Ionian olive leaves. Ghost-eyed, antediluvian, they darted upward, into the waiting, handheld nets, and then the sailors dropped everything to dash with their catch toward the galley like grooms carrying brides to a nuptial bed, one slit to yank the cartilage from white-purple flesh tossed without ceremony into a smoking skillet, trickled with lemon and oil, a pinch of salt, and eaten barely stilled, still tasting of the sea that had not yet registered its loss. That’s the image that comes back to me, the feast of the squid, and thereafter we passed our evenings playing cards or ferried into port after a dinner of oily moussaka by one of the ancient coal-burning tenders that made the rounds like spark-belching taxis among the vessels lying at anchor, and the gargantuan rats drinking from the scuppers, and the leering prostitutes in the harbormaster’s office, and the mango batidos Mike preferred to beer, and the night we missed our ride back to the ship and walked until the cafes closed and slept at the end of a long concrete breakwater, and the sky at first light a scroll of atoms, and the clouds at dawn as if drawn from a poem by Wallace Stevens, tinct of celadon and cinnabar and azure, and the locals waking on benches all around us, a whole neighborhood strolling out to squat and shit into the harbor, and then, piercing the clouds, aglow with sunlight for which the city still waited, the volcano—we’d never even guessed at its existence behind a mantle of perpetual mist—Pico de Orizaba, snow-topped Citlaltépetl like the sigil of a magus inked on vellum, and everything thereafter embellished by its hexwork, our lives forever stamped with that emblem of amazement, revelation, awe.

Praia dos Orixás

for Robert Hass

1

Farther north we came to a place of white sand and coconut palms, a tumbledown government research station, seemingly abandoned, no one in sight but sea turtles lolled in holding tanks along the edge of the beach. The ocean was rough, riptides beyond a shelf of underlying rock, water a deep equatorial green. We swam. Rested. Hid from the sun in the shade of the palms. A few miles on we found the fishing village by the inlet, the small restaurant with platters of squid and giant prawns on a terrace overlooking the harbor, manioc, sweet plantains, beans and rice in the lee of the cork-bobbed nets and the tiny cerulean and blood-orange fishing boats sheltered in the crook of the breakwater’s elbow. A boy selling sugarcane rode past on a donkey; white-turbaned women bent like egrets to the salt marsh. “There is no word for this in English,” said Elizabeth,

meaning, by this, everything.

Later: goats and dogs on barbed-wire tethers; children laughing beneath banana leaf umbrellas;

women hanging laundry on a red dirt hillside in a stately ballet with the wind.

2

The next day we headed back to the city, following the rutted dirt road along the coast until forced to a halt with the engine of our rented Volkswagen thumping and billowing a fatal tornado of smoke.

Fan belt, snapped in two.

It was difficult making ourselves understood in that place; they seemed to speak some backwoods dialect, or else the language failed us completely; neither Anna’s schoolbook Portuguese nor J.B.’s iffy favela slang brought any clear response. People beneath strange trees ignored us in the darkness, or watched with an air of unhappy distrust, or disdain, or possibly compassion.

Although we couldn’t see the beach, a sign by the road read Praia dos Orixás.

Eventually, one man took pity upon us, running home and returning with a fine black fan belt fresh in its package, a fan belt big enough for a tractor, impossible to jury-rig to that clockwork machine, and yet no matter how we contrived to explain ourselves, no matter what gesticulations we employed, what shadow play, what pantomime, we could not make him see that his gift would not suffice. No good! Too big! We held the broken belt against his, to display their comic disparity, but the man only smiled and nodded more eagerly, urged us to our task of fitting the new piece, happy to be of assistance, uncomprehending. Won’t fit! Too big! Thank you, friend!

Hopeless.

In the end, money was our undoing, those vivid and ethereal Brazilian bills stamped with the figures of undiscovered butterflies and Amazonian hydroelectric dams. I forget whose idea it was to pay the man for his kindness, but no sooner had the cash appeared in our hands than he at last gave vent to his anger and frustration, insulted by our mistaken generosity, hurling epithets that needed no translation, and so, as the crowd approached, menacingly, from the shadows,

or perhaps merely curious, or possibly protective,

we jumped in the car, still smiling, waving our arms like visiting dignitaries, desperate to display the depths of our goodwill but unwilling to risk the cost of further miscommunication,

and drove away with a gut-wrenching racket into the chartless and invinc

ible night.

3

What follows is untranslatable: the power of the darkness at the center of the jungle; cries of parrots mistaken for monkeys; the car giving up the ghost some miles down the road; a crowd of men with machetes and submachine guns materializing from the bush, turning out to be guards from a luxury resort less than a mile away; our arrival at Club Med; the rapidity of our eviction; our hike to the fazenda on the grounds of the old mango plantation where we smoked cigars and waited for a ride; the fisherman who transported us home with a truckload of lobsters bound for market.

By then another day had passed.

It was evening when we came upon the lights of the city like pearls unwound along the Atlantic, dark ferries crossing the bay, the patio at the Van Gogh restaurant where we talked over cold beer for uncounted hours. That night was the festival of São João, and the streets snaked with samba dancers and the dazzling music of trios elétricos, smell of roasting corn and peanuts, fresh oranges, firecrackers, sweet jenipapo, veins of gold on the hillsides above the city where flames ran shoeless in the fields among the shanties, warm ash sifting down upon our table, tiny pyres assembled around seashell ashtrays and empty bottles as the poor rained down their fury upon the rich. That night the smoke spelled out the characters of secret words and shadows were the marrow in the ribs of the dark. That night the stars fell down,

or perhaps it was another.

That night we yielded to the moon like migrating sea turtles given over to the tide-pull.

That night we clung together in the heat until dawn as the cries of the revelers ferried us beyond language.

That night we spoke in tears, in touches, in tongues.

Kingdom of the Sea Monkeys

When I close my eyes the movie starts, the poem rises, the plot begins.

Falling asleep it comes to me, the novel I will never write, in semaphore flashes against my eyelids, flames from a torpedoed ship reflected on low clouds, flames abstract as green fingers, steam-machinery assembled from blueprints of another era, engine-gush of hot ash, a foliage of fears as lush as prehistoric ferns.

Up rises chaff from the threshing floor, up rises moondust, city smoke, pulses of birdcall, voices chopped by wind into mews and phonemes.

The mind in the true dark at 3 A.M. when the electricity goes out with a bang—circling the ambit of consciousness, listening, probing, defending the perimeter, as long ago, fending off wolves with sharpened sticks when the fire died.

The perfecting of art, according to Kierkegaard, is contingent upon the possibility of gradually detaching itself more and more from space and aiming toward time,

a distinction analogous to that between perception and insight,

how the mind navigates like a bat, sometimes, soaring through its cavern via echolocation.

Other times it rests, perfectly still, like a bowl of pond water, a pure vessel in which the sediment, stirred up like flocks of swifts at dusk, swirls and drifts and settles, until its next disturbance, its next cyclonic effulgence.

Swirl, drift, settle.

It is the outside world that creates the self, that creates the sense of continuity on which the self depends—not the eyes, not the eyelash diffusing light, not the hands moving through the frame of observation, but the world.

We anchor ourselves within the familiar, like boats on an immensity of water.

Different day to day, yes—as the boardwalk of a town outside Genoa with its old carousel and honey-flavored ice cream cones differs from a plain of sagebrush in Nevada—different and yet always and immediately recognizable. Ah, there it is again, the world. And so I, too, must still be here, within the container of myself, this body, this armature. As long as I can see out I can see in.

Therefore it is only through others that we know ourselves.

Therefore the limits of our compassion form the limits of our world.

Still our lives resemble dreams, luminous tapestries woven by a mechanism like the star machine at the planetarium, realms of fantastic desire and possibility, like the kingdom of the sea monkeys promised in the back pages of comic books of my childhood, the King of the Sea Monkeys with his crown and trident, his coral-hewn castle with pennants waving. That so much could be obtained for so little! And then the licking of postage stamps, and the mailing away, and the waiting.

Or perhaps it is less like a dream than a visionary journey,

to pilot the vehicle of consciousness through the turmoil of reality as if crossing the heart of a continent,

shadow of a hawk on asphalt clear as a photograph

as you rise from rich valleys into snowy mountains, black trees, meltwater, the striations of snow melting around the tree trunks like the growth rings within the wood of the trees themselves, layered accretions, historical pith.

Such a sad awakening it was, the day the sea monkeys arrived in the mail, no proud sea monarch or tiny mermaid minions, no castle, no scepter, no crown, just a little paper packet of dried brine shrimp which, tumbled into a fishbowl, resembled wriggling microscopic larvae, resembled sediment in pond water, swirling and drifting and settling.

Where is the King of the Sea Monkeys, the ruler of all memory?

Lost, and with him his kingdom, vanished like Atlantis beneath the waves, while we cling to life rafts and tea chests amid the flotsam,

old movies projected like messages in bottles within the green-glass lyceums of our skulls.

Awakening, yes, as if startled from a dream.

As when, driving in heavy rain, you cross beneath an overpass and the world leaps with mystifying clarity at the windows of your eyes.

Philadelphia

Late dinner at a dark cafe blocks from Rittenhouse Square, iron pots of mussels and Belgian beer and a waiter eager to snag the check and clock out. Such are the summer pleasures of his work—winding down to a glass of red wine, catching the windowed reflection of a girl as she passes, counting the take upon the bar, thick roll of ones and fives, palming the odd ten smooth against zinc and polished walnut, the comforting dinginess of American money, color of August weeds in a yard of rusting appliances, hard cash, its halo of authority, the hands’ delight in its fricatives and gutturals, its growl, its purr, gruff demotic against the jargon of paychecks on automatic deposit with social security deductions and prepaid dental, realism vs. abstraction, a gallery of modest canvasses, more landscapes than still lives, steeples of the old city with masts and spars, a vista of water meadows with fishermen hauling nets in the distance, women collecting shellfish in wicker panniers. It yields enough to sustain us, after all, the ocean of the past. We’ve paid. The waiter pockets his final tip and throws down his apron and walks out into the warm night of dogs splashing in public fountains and couples on benches beneath blossoming trees and soon enough we follow, arm in arm across the cobblestones, looking for a yellow cab to carry us into the future.

Tabernacle, New Jersey

is not the place I thought it was. All these years, crossing the dwarf-pine coastal midlands, the map of New Jersey gone AWOL from the road atlas, what I’d remembered as Tabernacle was actually Chatsworth, two old colonial towns, ten miles apart, peas in a pod, nothing could be more similar and nothing could be more distinct. Chatsworth, I guess, was named by the homesick for a town left behind in England, while Tabernacle implies not only a house of worship but a sanctuary and a shelter, a dwelling place and a covenant, an immaculate coal in the hearth of the New World, invested today in exurban restoration, garden centers and antique marts, new subdivisions in the old peach orchards, the historic church signed and posted for day-trippers out from Philadelphia. Tabernacle is a sign of things to come while Chatsworth is purely a thing of the past, a place so momentary its passage is forgotten even before its official contemplation—was that it?—ramshackle houses set back beneath shade trees, front porches sagged and winded, a poster for the annual BBQ & turkey shoot at the Antler Hall, a roadhouse and general store at the crossroads of the Pine Barrens, that comical b

ackwater of forgotten towns, Batsto and Ong’s Hat, Leektown and Double Trouble, so named when muskrats gnawed through the town dam two times in a single month. Muskrats. Twice.

What I like about Chatsworth is its sandy transience, its ageless and indelibly American dereliction. People came to Chatsworth, lived for a while, and moved on. They settled down, hunted deer, kilned bricks, scrounged the deposits of pig iron from the soil, harvested the cranberry bogs, chopped down the pine trees and burned them for charcoal, raised up kids for a generation or two, then headed out for greener pastures, taking Chatsworth with them and leaving Chatsworth behind. A town like Chatsworth could be anywhere, right at home among tired Tidewater tobacco fields or the chicken houses of the Eastern Shore, along the old wagon roads at some ford of the Potomac, the Susquehanna, the Delaware, the James, anywhere at all in the majestic and underappreciated Mid-Atlantic region, which is home to me, central and definitive, though for that matter you could find Chatsworth in most of Appalachia and scattered throughout the South, and into the riverine Midwest, Ohio and Illinois and Missouri and Iowa, and so into the plains, and following the Oregon Trail across the mountains and into the apple orchards of the Pacific Northwest, and even in the altogether unnatural badlands of Utah where, once, lonely to the point of desperation, I passed through just such a place on a Sunday afternoon when the volunteer firemen’s picnic was in progress, a group of families eating hot dogs and buttered corn, some kids with red and yellow balloons, people waving in kindly invitation as I slowed to a crawl, and thought about stopping, and drove on.

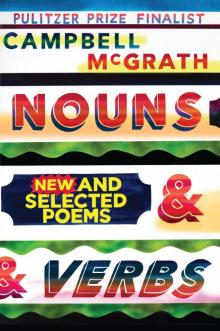

Nouns & Verbs

Nouns & Verbs