- Home

- Campbell McGrath

Nouns & Verbs Page 2

Nouns & Verbs Read online

Page 2

I want to feed a Happy Meal to a cheetah.

I’m tired of not being Nicanor Parra.

I want to say, basically, fuck you to poetry

with all its outlandish maunderings.

Magic numbers piss me off,

I’m bored by rubrics and party lines,

the bloody giblets of nostalgia disgust me.

The past is a sadly inadequate word

for what we’ve been through,

earthly existence, this life, right here.

Nature ruled the planet long before our entrance

yet surely its reign was nothing more

than a pulsating machine-works of appetite,

ultra-vivid but purely mechanical,

a rococo cuckoo clock

trivialized by its own clownish reality,

its too literal presence in the moment.

Is the air in which they disport

truly so wonderful, vainglorious swallows

making a spectacle of themselves

as if to prove their familiarity with a drama

in which we resemble minor characters

bumbling onstage in the final act?

Of course we admire the birds and trees

but their diffidence insults our dignity

and when, inevitably, we lash out in anger,

nature has none but herself to blame,

for we, too, bear the mark of her flawed manufacture

from our first, gasping, egg-damp cries.

To be human is to be scissor-cut

in bold strokes from imperfectly pressed paper,

our brains, like huge unblooming peonies,

tug our bodies inexorably earthward,

while language resembles a clutch of party balloons

intended to lift us to salvation

but there is so much that cannot be captured

in pink latex and self-reflective Mylar—

snow falling on the temple gardens of Kyoto,

the heroic loneliness of cemetery flags,

even our drive along the Palisades Parkway

on a summer day so long ago.

The past—what an awful word

for something we can never get beyond,

no matter how restlessly we travel.

The Palisades Parkway comes to an end

in Rockland County, New York,

just beyond the abandoned hamlet of Doodletown.

All good things must come to an end.

But not all good things end in Doodletown, New York.

Four Love Poems

1. NOX BOREALIS

If Socrates drank his portion of hemlock willingly,

if the Appalachians have endured unending ages of erosion,

if the wind can learn to read our minds

and moonlight moonlight as a master pickpocket,

surely we can contend with contentment as our commission.

Deer in a stubble field, small birds dreaming

unimaginable dreams in hollow trees,

even the icicles, darling, even the icicles shame us

with their stoicism, their radiant resolve.

Listen to me now: think of something you love

but not too dearly, so the night will steal from us

only what we can afford to lose.

2. AURORA PERPETUA

O tulip, tulip, you bloom all day and later sway

a deep-waisted limbo above the dinner table,

waiting for a coin to drop into your well,

for the stars to pin your stem to their lapel.

Soon, on ocean winds, dawn cries its devotion,

our world entranced once more into being.

Let go your sumptuous rage, darling.

All this awed awakening is a form of adoration.

What’s born in that fountain of salt and spume,

of spackled sea monsters and gardenia perfume,

is everything blossoming ever amounts to:

an hour of earthly nectar, a single drop of dew.

3. IMPERIUM FORTUNATUS

We were born to rule an empire together, but which one?

Empire of antique tinsel and gingerbread mansions,

of sentimental melodies on black scratchy gramophones?

Stars are piping their bossa nova rhythms

through the wires again tonight, shuffle left, shuffle right.

Even now I’m startled from a familiar dream

to chart the chords, to note the steps of passing satellites.

And then back to what was, in its way, a more perfect union.

So you see I’ve lost the essential distinction—

which is our dominion, darling, which the barbarian realm?

Come, I’ll shed this common cloth, you slip your silken gown.

Let moonlight be our mantle, and ecstasy our crown.

4. LUX AUSTRALIS

Early evening honey and whiskey, that sweetness,

bees in the ever-blossoming tresses

of your hair, darling, the touch of a hand

like water in a parched man’s cup,

the way memory chimes its silver-stringed guitar

like moonlight on a spiderweb,

milkweed stalks against rusted-out pickup trucks,

their wandering seed our only constellations,

bells in the velvet darkness before dawn,

that mystery, that consolation,

worn-down paths we walk fortified by trust in simplicity

and cans of beer in wind off the soon-to-be-planted fields.

O let us reseed the garden and eat vegetable soup

and never go to town, not even for bread.

Let us inhabit this moment forever and ever.

Live with me always in the scrap heap of my heart.

Andromeda

Already the countdown has begun:

four billion years until Andromeda

collides with the Milky Way, rupturing

forever that footpath through the forest

of dreamers’ jewels. I would scoff,

if I did not recall the tracery of fine hairs

swirled across an infant’s skull

like the softest of inbound galaxies.

Andromeda, all your starry wonders

cannot salve the ache of baby teeth

chanced upon, this 2 A.M.,

at the bottom of a bedside drawer.

My Sadness

Another year is coming to an end

but my old t-shirts will not be back—

the pea-green one from Trinity College,

gunked with streaks of lawn-mower grease,

the one with orange bat wings

from Diamond Cavern, Kentucky,

vanished

without a trace.

After a two-day storm I wander the beach

admiring the ocean’s lack of attachment.

I huddle beneath a seashell,

lonely as an exile.

My sadness is the sadness of water fountains.

My sadness is as ordinary as these gulls

importuning for Cheetos or scraps

of peanut butter sandwiches.

Feed them a single crust

and they will never leave you alone.

Patrimony

In Europe, someone is always stealing famous paintings,

as if it were so easy to dehistoricize the academy,

to sever a father’s tongue and replace the past

with mute quadrilaterals of dust. Out the window

of the overnight bus maple leaves are dying in style

while the great country and western songs I love

remain baroque, sentimental and full of life.

Same tangle of grief and salvation, same wife,

same kids, same house, same city—

what changes is the book you are writing

and the faces around the table discussing the grass

Walt Whitman beco

mes on the earth within us.

Imagine that gallery full of stolen masterworks

and then imagine the museum of the never-created,

Schubert’s slide guitar, the graphic novels of El Greco.

Imagine the movies Sappho would have made!

Reading Emily Dickinson at Jiffy Lube

Sitting in the waiting room at Jiffy Lube, reading Emily Dickinson and watching a rerun of Matlock, I realize that my life is exactly like this moment, when Andy Griffith turns to the jury, beaming his most grandfatherly, country-wise smile, ready to unmask the killer, and says—and says—well, they’ve cut to a commercial, I don’t know what he says.

But then it wouldn’t be much of a mystery if I did.

Anyway, I am old enough to know that guilt and innocence are relative virtues on daytime TV, and that even the present instant, with its brash odors of coffee and newspaper ink, its flocculent light, even this empire of the senses is an abiding enigma.

If I should live to be one hundred, in the year A.D. 2062, I will have seen the 200th anniversary of the annus mirabilis in which Emily Dickinson wrote three hundred poems while the Civil War raged at its most horrifying intensity,

and my own birth, half a century ago, will mark a fulcrum between those time-vaulting poles—

between the bloodletting at Shiloh and Antietam,

while Emily, in her solitude, penciled stanzas on scraps of wrapping paper and torn envelopes, cuttings from a landscape of fertile ingenuity, a marvelous mental garden, the undiscovered continent of the self—

and the imponderable far-off future,

when new technologies will empower us and new populations seethe with needs and the oceans shall have risen to consume this fragile sandbar on which I have injudiciously staked my claim,

and if so, this moment, right now, would mark a similar midpoint in my own life, though five more decades seems unlikely,

and I am old enough to know that I will never be Emily Dickinson.

I am old enough to recognize that justice is a prime-time fable, that the moon smiles down upon the savage and the merciful alike, old enough to understand that I will never live in the desert, which makes me sad, though I fear the desert instinctively and would never want to live there.

Still one takes comfort in imagining the contours of a life in Arizona, a life of Franciscan austerity in Bend, Oregon.

One imagines all the barrier islands and beach towns up and down the East Coast swallowed by the tantalizing waters of the Atlantic Ocean, all the taffy shops and nail salons of the Jersey Shore, the skate punks in the parking lot of the convenience store and the headbanger at the register of the convenience store and the buying of condoms and six-packs of Smirnoff Ice, a place so inimitable and ass-kicking I can already hear the pulsating guitar-and-glockenspiel intro of “Born to Run” unrolling its red carpet to my heart, a song that remains a primary text of American male identity, like The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, and being hokum, being a confection of swagger and tattered glory, subtracts nothing from its legend, and when I think of Bruce Springsteen’s improbable rise to eloquence, his silent and bitter father, his bantam insecurities, his boardwalk voice and secondhand guitar, I am reminded that no act of self-expression is unrealizable here, and when I think of him now, defanged but uncorrupted, chugging through soggy Dust Bowl ballads—

as if New Jersey were not the mythic equal of Oklahoma, as if “Atlantic City” were not a folk song as potent as any of Woody Guthrie’s—

well, I guess we all lose our way, sooner or later, in America,

even Bruce Springsteen.

Oh, but there was a song sung, wasn’t there, eight maids a-milking and a bobtail nag, the morning after Thanksgiving and all the middle-aged stoners calling in to Z104 requesting REO Speedwagon?

There was a mystery solved, a day lived through, all sugar and oil, all lips and wind, a hat, a rabbit, a magic word.

Praise the sun’s masons assembling the sensorium from photons and scraps of subatomic shadow!

Praise images that leap from the mind like ninjas!

Praise Emily Dickinson’s folk-strumming daughters and Walt Whitman’s fuel-injected sons—forth-steppers from the latent unrealized baby-days!

Saying Goodbye to Paul Walker

My family is away for the weekend and I am home alone, cleaning out the garage, a troll-den of dust and termite wings and rusting paint cans. At five o’clock I bolt a new handle on the garage door, pop a beer, and declare victory; at seven I order in the delicious vaca frita from Latin Café and at ten I am drinking a bottle of Spanish wine watching Furious 7, the latest installment of the witless car-chase movie franchise, starring Vin Diesel, the Rock, Paul Walker, et alia, as an improbable band of maverick, shoot-’em-up, thrill-seeking auto jockeys. This episode is notable for its particularly cockamamie action sequences, general high spirits, and of course the death—in real life, just as the film had finished shooting—of Paul Walker. Watching now, it seems almost cruel to notice how earnestly and unironically square-jawed he is, which in no way distinguishes him from his current cast mates, a menagerie of hambones, blockheads, and sneering no-goodniks. Saying goodbye to Paul Walker should not be hard, and yet there was something different about him, wasn’t there, a special light in his cool blue eyes, as if he were sharing a secret with us, as if he were twinkling and smirking not merely at the terrible dialogue he is compelled to utter, but at the ridiculous good fortune of his life. Saying goodbye to Paul Walker should be a piece of cake but it isn’t, and though it makes no sense I’ve got tears in my eyes as they run a montage of farewell shots at the end of the movie—“You will always be my brother,” Vin Diesel intones, v.o.—and we know that he is truly dead, that Paul Walker IV, born in Glendale in 1973, son of Cheryl and Paul III, has passed on to another plane—and yet within the movie’s master narrative Paul Walker is not dead at all, he has merely “retired” and so will live forever in that phantom, cloud-lit, celluloid eternity, which is a preposterous but oddly comforting metafiction, like telling a child his tiny turtle has escaped out the window and gone to live in the lily pond on the golf course, when of course you found the poor thing shriveled up like an old apple core beneath the couch. Saying goodbye to Paul Walker may not be a milestone in cinematic history but it feels like the end of something important. Saying goodbye to Paul Walker means saying goodbye to innocence and heroism and guileless blue-eyed optimism. Saying goodbye to Paul Walker means saying goodbye to Saturday matinees and the magical intimacy of a family growing up together, to my sons as they come and go to college in Chicago and hiking trips in Montana, as they surge forth into their fast and furious American futures. Saying goodbye to Paul Walker means saying goodbye to everyone and everything I have ever loved. That turtle wasn’t much, I suppose, but he meant a lot to some of us.

Cryptozoology

So long as kids still borrow the family car

to screw around joyriding

and tossing crushed beer cans out the windows

I shall feel at home in these United States.

Thank god for Henry Ford.

Thank god for Texas,

minus which our fabled republic

would resemble a box of jelly donuts

without no goddamn coffee.

Perhaps I’m naive

but if the Tasmanian wolf is still alive anywhere

it’s in the wail of feedback and amp-garbled blues chords

of some insane teenage garage band, isn’t it,

isn’t it, I mean—isn’t

it?

Another Night at Lester’s

1.

Many of the voices I’m hearing these days

belong to actual people;

others resemble Ashbery poems recited by preschoolers.

Self-importance is something I learned from a self-help manual; pretentiousness I come by naturally.

My thanks to the generations yet to come

for their preorders of my

Collected Works.

2.

In the next six hundred poems I’m going to read

tonight all words will be buzzwords,

all metaphors ink-edged, all images

pitched to tickle the funny bone and melt the heart

and vent some spleen

and pickle my liver and give you the finger.

3.

I had a thought and then I had a thought

and then I had another thought.

Check it out, the pics are on Instagram.

People who bought the items in your cart

also bought books about André Breton and Lindsay Lohan,

which tells you what, exactly?

4.

This has been a test of the Emergency Broadcast System.

Wrong button.

This has been an Audible audio text recording—

thank you for listening to Campbell McGrath’s poem

“Another Night at Lester’s,”

based on the novel Push, by Sapphire.

Sleepwork

I. MY HISTORY

Nothing much happens. And so we begin.

So we begin to negotiate the alphabet of regrets

and passions such chronicles are written in.

Begun and, already, done. So soon, so easily?

In the end the house falls down. And so do we.

II. READING LATE

Reading late, globed in shaded lamplight,

the family long asleep, the house restored

to its timbre of groaning night sounds,

a nocturne of peeping tree frogs, the soft moans

of palm fronds and termite-ridden beams.

III. SYNTAX

Deep, sensual pleasure of the book—

crack of a taut spine, allure of the page

and its must, its skitter, its ply—

life as it exists

there, as we exist in it,

reflections in a drop of mercury,

all the letters

of all the alphabets of every language

harnessed to meaning by syntax.

IV. A PAPER BOAT

At last I can be free and alone

and fold my news

into a paper boat I step into and set sail at once

to live my life inside a dream.

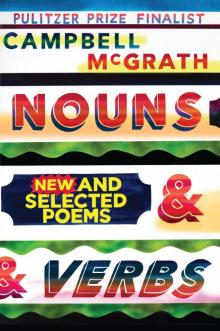

Nouns & Verbs

Nouns & Verbs